TUESDAY, 9 NOVEMBER 2010

Good news for knuckle crackers

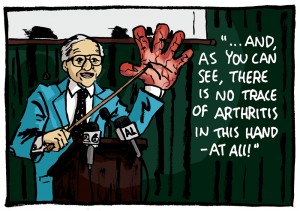

A fifty year study has finally reached its climax and come to the conclusion that knuckle cracking does not cause arthritis. Finally, you can quieten all those who love to smugly tell you that you are slowly damaging your joints. Just point them in the direction of Donald L Unger, the 2009 Ig Nobel Prize winner for medicine. He came up with an ingenious experiment: for 50 years, he cracked the knuckles on his left hand no less than twice a day, whilst leaving his right knuckles untouched. This means that the knuckles on his left hand were cracked at least 36,500 times. At the end of the experiment, both hands were examined for the presence of arthritis, and not only was none found, but there was no apparent medical difference between his hands at all. Kudos to Mr. Unger and his left hand. Richard Thomson

A fifty year study has finally reached its climax and come to the conclusion that knuckle cracking does not cause arthritis. Finally, you can quieten all those who love to smugly tell you that you are slowly damaging your joints. Just point them in the direction of Donald L Unger, the 2009 Ig Nobel Prize winner for medicine. He came up with an ingenious experiment: for 50 years, he cracked the knuckles on his left hand no less than twice a day, whilst leaving his right knuckles untouched. This means that the knuckles on his left hand were cracked at least 36,500 times. At the end of the experiment, both hands were examined for the presence of arthritis, and not only was none found, but there was no apparent medical difference between his hands at all. Kudos to Mr. Unger and his left hand. Richard ThomsonNaming cows increases milk production

We are all used to calling our pets by names, but what about cows? Scientists at Newcastle University surveyed 560 farms in the UK and found that farmers who called their cows by names had a 258 litre increase in milk yield (per cow, per year) compared to the farmers who didn’t. Catherine Bertenshaw, one of the scientists involved in the study, believes that naming the cows resulted in more positive human interactions with the animals and that this is what made them so much more productive. The actual naming itself is not so important, rather it is how the naming changes the interactions between the farmers and the animals. Fearful cows produce more cortisol, which interferes with milk production. The same thing is known to happen to human mothers. Positive interactions with the cows reduce their fearfulness towards humans, and so they are in a more relaxed state when it comes to the milk production. Although this study first made people laugh, it is now making farmers think seriously about what to name their cows. Xia Chen

We are all used to calling our pets by names, but what about cows? Scientists at Newcastle University surveyed 560 farms in the UK and found that farmers who called their cows by names had a 258 litre increase in milk yield (per cow, per year) compared to the farmers who didn’t. Catherine Bertenshaw, one of the scientists involved in the study, believes that naming the cows resulted in more positive human interactions with the animals and that this is what made them so much more productive. The actual naming itself is not so important, rather it is how the naming changes the interactions between the farmers and the animals. Fearful cows produce more cortisol, which interferes with milk production. The same thing is known to happen to human mothers. Positive interactions with the cows reduce their fearfulness towards humans, and so they are in a more relaxed state when it comes to the milk production. Although this study first made people laugh, it is now making farmers think seriously about what to name their cows. Xia ChenBeer bottle brutality

In a study appropriate for an episode of CSI, forensic pathologist Stephan Bolliger and his colleagues looked into whether empty or full bottles of beer make better weapons, and whether they are able to fracture a human skull. After being asked these questions in court, and perhaps after a few beers, the researchers decided to measure the minimum energy required to break both full and empty bottles of beer. They attached the bottles to a pinewood board using modelling clay and then dropped a steel ball from various heights onto the bottles. The modelling clay was meant to represent the soft tissue surrounding the skull and the pinewood board was meant to act like the boney skull and distribute the impact of the ball. They found that empty beer bottles required significantly more energy to break (40J) than full beer bottles (30J); with the breaking threshold of the human skull ranging from 14.1J to 68.5J, it’s hard to say which one will break first. So it may be better to get smashed over the head with a full bottle of beer than an empty one, but either way you could end up with a fractured skull. Nicola Stead

In a study appropriate for an episode of CSI, forensic pathologist Stephan Bolliger and his colleagues looked into whether empty or full bottles of beer make better weapons, and whether they are able to fracture a human skull. After being asked these questions in court, and perhaps after a few beers, the researchers decided to measure the minimum energy required to break both full and empty bottles of beer. They attached the bottles to a pinewood board using modelling clay and then dropped a steel ball from various heights onto the bottles. The modelling clay was meant to represent the soft tissue surrounding the skull and the pinewood board was meant to act like the boney skull and distribute the impact of the ball. They found that empty beer bottles required significantly more energy to break (40J) than full beer bottles (30J); with the breaking threshold of the human skull ranging from 14.1J to 68.5J, it’s hard to say which one will break first. So it may be better to get smashed over the head with a full bottle of beer than an empty one, but either way you could end up with a fractured skull. Nicola SteadIf you have a wacky research story, let us know and we may include it in the next issue of BlueSci