SATURDAY, 7 MAY 2011

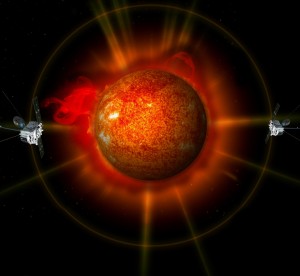

Nasa have moved the twin STEREO imaging probes into position on opposite sides of the Sun, revealing our star for the first time in all its 3D glory. The telescopes on STEREO are sensitive to four wavelengths of ultraviolet radiation, allowing them to trace key aspects of solar activity, including solar flares, tsunamis and magnetic filaments, which will greatly advance not just theoretical solar physics research, but also space weather forecasting.Previously, active regions could suddenly emerge from the far side of the Sun, spitting flares of intense electromagnetic radiation towards the Earth that can cause severe disruption to airlines, power supplies and satellite operations. With STEREO, active regions of the Sun can now be tracked, so that scientists can predict with accuracy when solar radiation is likely to reach dangerously high levels. Solar storms on their way towards other planets can also be tracked, which holds great importance for NASA missions elsewhere in the solar system.

Monitoring the entirety of the Sun’s surface could also help to solve some of the many fundamental puzzles underlying solar activity: researchers have long suspected ‘global’ interactions between eruptions on opposite sides of the Sun, and STEREO provides observational data to test these theories. With higher resolution images on their way, it seems that the sky’s the limit for solar physics. Katy Wei

Human migration out of Africa

It is widely accepted that humans originated in Africa, and current theory states that modern humans did not leave their original homeland until 65,000 years ago, with the exception of a few isolated populations. However, a team working in Jebel Faya in the United Arab Emirates have proposed a much earlier dispersal into the Arabian Peninsula.

The team discovered tools which are at least 95,000 years old, suggesting that modern humans migrated across southern Arabia around 125,000 years ago when the area was more hospitable. Some of the tools found at Jebel Faya show notable similarity to those made by contemporary Homo sapiens in Africa, leading theauthors to suggest that modern humans have lived continuously in the area until at least 40,000 years ago. However, this directly contradicts genetic evidence stating that populations were constantly wiped out and replaced by the changing climate during this period. Additionally, the team found no human fossils and their dating evidence was strongly inconsistent.

Whilst it seems likely that Jebel Faya was inhabited by modern humans earlier than was previously thought, the humans probably only stayed for a short period, and other human species may have also occupied the area. Whilst this is a promising lead, more work is needed to reliably establish the role of Arabia in early migration of H. sapiens out of Africa. Jonathan Lawson

New mosquito subgroup solves malaria mysteries?

Malaria is responsible for around one million deaths in Africa alone every year. The disease is transmitted to humans from bites by Anopheles mosquitoes that carry the Plasmodium parasite.

An international team of scientists describing populations of Anopheles gambiae in West Africa have discovered a new subgroup of the mosquito that may hold the key to a better control of malaria. The genetically distinct subgroup, called ‘Goundry’, was identified by comparing genetic markers and mutations in mosquito genomes. As well as being genetically distinct, Goundry was found to have an important behavioural trait which surprised many scientists; rather than living primarily inside people’s homes, the new strain lives outside.

This behaviour has potential implications for malaria eradication programmes that have previously focused on preventing mosquito bites in the home. The researchers working on Goundry have already found that the new subgroup is more susceptible than other strains to picking up the Plasmodium parasite from infected blood. The next step is to ascertain whether they commonly bite humans. If the newly discovered mosquitoes are found to be an important transmitter of malaria, eradication programmes must shift their focus to include outdoor bite prevention too. Imogen Ogilvie