THURSDAY, 1 OCTOBER 2009

Like many children, Jim Bagian dreamed of going into space. By the age of 12, he realised that perhaps it wasn’t the most realistic of aspirations. “It was like wanting to be president of the United States, or maybe as unrealistic for me as becoming the British Prime Minister.”Having outgrown his desire to become an astronaut, Jim attended engineering school followed by medical school and trained to become a doctor. It was here, while between surgeries, that he saw a NASA advertisement calling for applications for astronauts.

Despite being discouraged by his lack of the ‘right kind of flying experience’ he had gained while at engineering school, Jim applied anyway. To his surprise he was selected to become a space shuttle astronaut and, at the time, the youngest person to be selected. Jim joined NASA in 1980 and went into space on two separate occasions for five and ten days respectively in March 1989 and June 1991.

The main task during Jim’s first mission was to place a satellite into a geosynchronous orbit. Simultaneously they were also conducting a number of science experiments. Jim was looking at a treatment for space motion sickness – a potentially debilitating and dangerous consequence of weightlessness.

“The symptoms sound like motion sickness that you might get on a boat or car or whatever, but it had never been successfully treated. It was a major problem. About 75% of all first time flyers get sick to one degree or another. Sometimes it’s just minor, stomach pains or such, but others can be vomiting every ten minutes.”

James wanted to try a drug already used on Earth, arguing that possible side-effects were minimal compared to the potential symptoms. During his flight, the drug was tested on several fellow astronauts and it worked with nearly a 100% success rate.

“Space motion sickness had a lot of impact on how we did missions because we had to allow for people being sick. Now if they’re sick, you inject them and in twenty minutes they’re good to go.”

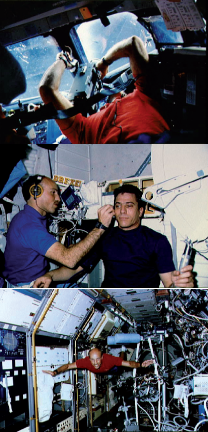

Jim’s time in space was extremely tightly choreographed. Every five minutes were accounted for except for bathroom breaks that “you had to squeeze in” somehow. Their schedules were also intertwined so being off yours could affect others.

“Everything is accounted for: when you’re doing this experiment, when you’re doing that experiment, when you’re using the computer, when you’re downloading data, when you’re uploading data, how much power you’re pulling on your experiments – because if all the high powered experiments ran at the same time, you couldn’t supply them.

“You can’t be like ‘Well, maybe I’ll do that experiment later rather than now,’ because that will have huge ramifications. Will you be able to get the data stream downloaded and get the scientists the information on the ground? Will you have enough power to even do it? So you weren’t sitting around thinking ‘maybe I’ll look out the window a little bit more’ or ‘maybe I’ll have tea now’ – that wasn’t happening. You were very busy the entire time.”

Jim describes weightlessness as like being in a swimming pool whose water is the same temperature as your skin – essentially it feels like nothing, and you quickly adapt your behaviour. Your reflexes when you ‘drop’ something become redundant and you learn than when you put something ‘down’, you have to just let it float so that when you turnaround to retrieve it, it may only have moved an inch.

By all accounts, the view is quite spectacular: “You can see a tremendous amount of detail. Looking at the sea with your eyes, it’s a bunch of different blues. You can see cold water upwellings. You can see a ship’s wake a thousand miles long and see the ship up at the front. You can see in some cases roads with your naked eye.

data, when you’re uploading data, how much power you’re pulling on your experiments – because if all the high powered experiments ran at the same time, you couldn’t supply them.

“You can’t be like ‘Well, maybe I’ll do that experiment later rather than now,’ because that will have huge ramifications. Will you be able to get the data stream downloaded and get the scientists the information on the ground? Will you have enough power to even do it? So you weren’t sitting around thinking ‘maybe I’ll look out the window a little bit more’ or ‘maybe I’ll have tea now’ – that wasn’t happening. You were very busy the entire time.”

Jim describes weightlessness as like being in a swimming pool whose water is the same temperature as your skin – essentially it feels like nothing, and you quickly adapt your behaviour. Your reflexes when you ‘drop’ something become redundant and you learn than when you put something ‘down’, you have to just let it float so that when you turnaround to retrieve it, it may only have moved an inch.

By all accounts, the view is quite spectacular: “You can see a tremendous amount of detail. Looking at the sea with your eyes, it’s a bunch of different blues. You can see cold water upwellings. You can see a ship’s wake a thousand miles long and see the ship up at the front. You can see in some cases roads with your naked eye. I could even see the football field two blocks from my parent’s home.”

This spectacular clarity comes from the lack of atmosphere. When you’re looking down from orbit, you’re not looking through a lot of atmosphere which is already relatively thin only a mile up. In contrast, when you’re looking horizontally, you’re often looking through miles of atmosphere that seriously impedes your ability to see objects far away. The difference is incredible. According to Jim, from 180 miles up and with a regular pair of binoculars “you can see the surf break over Polynesian islands and the palm trees on the beach.”

Perhaps the oddest thing to happen to Jim occurred during the first couple of hours of his first mission. The shuttle had just settled into orbit, opened the payload doors and was approaching the night time side of Earth, when he saw something rather strange.

“I saw what appeared to be a red flashing light – like a rotating red beacon on an aeroplane and it seemed to be about 100 metres away. I was like, ‘what am I seeing here? Is this a UFO?’ It was there for about 30 seconds, flashing and then it went out.” Perplexed, James kept quiet but then 45 minutes later, it appeared again as they reached the daytime side of the Earth.

“And when it got to full daylight, I saw that is was a washer – the little metal disk with a hole in it – and it had probably been left there in a payload bay by a mechanic and had floated out into space and was in orbit with us and rotating, so at sunrise it would flash red as it caught the sunlight, flashing every second.”

The story gets stranger. When the crew returned to Earth he discovered that there was a bogus press report from someone claiming to have intercepted radio messages from the space shuttle saying that they had birthed a UFO in their payload bay. Jim had been identified as the person who had made the transmission. Years, even decades later, Jim would get calls from Hollywood producers keen for an insight into how the UFO had docked.

Jim has some solid advice on becoming an astronaut: “The fact is that you have to apply! I was 24 years old when I submitted my application and really didn’t think I stood a chance.”

“It’s very challenging. Most of it is not flying but getting ready to fly. So if you’re someone who doesn’t like doing some of the development work and you don’t like engineering, then you’re not going to like being an astronaut because that’s what most of your work is. Flying to me is the anti-climactic part. It’s a nice experience and all, but the satisfaction comes from making sure that the mission is possible to do.”

In all seriousness, Jim stresses that you should pursue you interests. His had inadvertently prepared him for a career as an astronaut. “I had done different things because I had a passion for them. Trying to fill out my resume and become an astronaut wasn’t on my mind. Yet all those things are what lead to me being selected. I wasn’t doing it to earn merit badges. If you’re doing things that you wouldn’t normally do, then maybe you’re preparing yourself for the wrong carear.”

Post-NASA, Jim became the chief patient safety officer and the director for the National Safety Centre of Patient Safety for the Department of Veteran Affairs and was given a carte blanche at a time before patient care was an established medical discipline. Medical errors can have serious consequences for patients and Jim has been able to use his skills as an engineer and physician to make dramatic improvements.

“This job didn’t exist until I had it. Nobody in the world had a job like this and when the person that ran it said, ‘safety is an issue will you come and look at it’, I thought absolutely, because I always chafed the way that medicine was run in that regard. This was an opportunity to make a difference.”

Chris Adriaanse is a PhD student in the Department of Chemistry and Sonia Aguera is a PhD student in the Department of Pathology.