SUNDAY, 19 MARCH 2017

“Without urgent, co-ordinated action by many stakeholders, the world is headed for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries which have been treatable for decades can once again kill.” This warning was given in 2014 by Dr. Keiji Fukuda, the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Assistant Director-General for Health Security. Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria develop mechanisms to survive even when threatened with antibiotics; this is not only a medical threat but also an economic one. Indeed, the World Economic Forum has identified the emergence of antibiotic resistance as a global risk beyond the capacity of any organisation or nation to mitigate alone, prompting the need for collaborative strategies.Our society relies heavily on the use of antibiotics for the treatment of common bacterial infections and for prevention of infection during routine operations. However, bacteria can evolve multiple methods of eliminating or inactivating antibiotics such as preventing antibiotic uptake, breaking down the drug, or speeding up its extrusion – to name just a few. Alarmingly, resistance is emerging even to drugs that are used as the ‘last resort’ against infections for which other antibiotics have not worked. A good example is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (also known as MRSA). In the late 1950s, methicillin was used to treat penicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus. Within ten years the bacterium developed resistance to methicillin as well. Since then, MRSA has become one of the most common hospital-acquired infections around the world, and has even spread throughout intensive animal farming operations and within the wider community.

...Resistance is emerging even to drugs that are used as the ‘last resort’ against infections

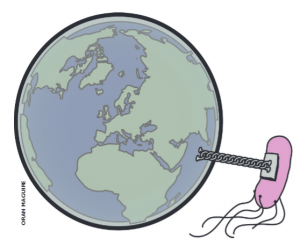

Many factors contribute to the emergence of antibiotic resistance worldwide. These include misuse of antibiotics, patients not completing their course of treatment, and the overuse of antibiotics in animal feed as a growth supplement. Crucially, with the rise in international air travel and increased human mobility, resistant bacteria can travel faster and further than ever before, with no respect for national borders. This means that one country’s ‘superbug’ is everyone’s problem, and therefore global concerted efforts are needed to contain and combat the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Image by Oran Maguire

Image by Oran MaguireIn a response to the need for concerted global action, the WHO published their Global Action Plan on antibiotic resistance in 2015. They outlined key strategic objectives necessary to ensure that treatment and prevention of infectious diseases with effective and safe medicines can continue. These range from simply raising awareness and improving sanitation and hygiene practices worldwide, to optimising use of current medicines in human and animal health and encouraging sustainable investment in research and development of new therapies. Despite these advances, however, no new classes of antibiotics able to treat systemic infections have been discovered since 1987. Recently approved drugs simply build on well-known previous classes of antibiotics, and are thus often quite susceptible to the resistance mechanisms that bacteria have already developed.

Research into new antibiotics is very challenging and expensive. A major problem is that pharmaceutical companies do not have incentives to invest in new research, despite the fact that there is immense unmet need and potential affluent markets. This is due to fears that resistance would soon emerge to any new therapy, meaning that the time for return on investment would be cut short. In addition, there is worry that new therapies, for which no resistance has yet emerged, could have their use restricted to only the most severe cases in an attempt to prevent resistance emerging, effectively reducing the patient population and market size for the new drug. These hurdles just add to the other normal challenges in pharmaceutical research. From the start of research, it currently takes 15 years for a marketable product to be produced, and failure rates are high, with only 1.5-3.5% of compounds making the distance.

...Pharmaceutical companies do not have incentives to invest in new research

With so little certainty of financial return, it is easy to understand why pharma companies are unwilling to make the investment. In 2014 the UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, commissioned economist Jim O’Neill to analyse the problem of rising drug resistance and propose concrete actions to tackle it internationally. Subsequently, in 2015, O’Neill published the review on antibiotic resistance, which was jointly supported by the UK government and the Wellcome Trust. Within it he details a model that emphasizes the importance of implementing measures rewarding drug developers based on the long-term benefit a drug can offer to society, rather than simply during the short time they are on patent. This would provide a more predictable market for those that develop drugs against critical pathogens, whilst getting rid of the notion that the sole way to make money in this market is to maximise the volume of sales.

Whilst global regulatory standards are important, there are ways in which they could be optimised to reduce costs for pharmaceutical companies without compromising patient safety. Harmonising drug approval processes globally to abolish the requirement for pharma companies to register new products in individual countries would considerably lower costs of pharmaceutical development. This is because often subtly different requirements must be met in each country, leading to the need for additional file submissions and negotiations, which both costs more and takes time. Speeding up approval processes would allow an effective increase in the period of time a company has exclusive rights to selling a new product before patent expiration, whereupon cheap alternatives can be released by competitors. Therefore, a new drug would have greater earning potential, making antibiotic development more financially attractive.

Funding for clinical trials, the most expensive part of drug development, by public bodies and regulators such as the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) and EMA (European Medicines Agency) is another potential option, and has been put into effect

Image by Oran Maguire. Bacteria have many mechanisms that are essential to their life processes.Each mechanism is a potential target for new drugs. However, drug developers need funding incentives to bring even a few to market.

Image by Oran Maguire. Bacteria have many mechanisms that are essential to their life processes.Each mechanism is a potential target for new drugs. However, drug developers need funding incentives to bring even a few to market.O’Neill’s 2015 review suggests a solution for streamlining the path for new antibiotics that also addresses antibiotic resistance: the creation of a designated ‘global buyer’ organisation, responsible for purchasing sales rights to antibiotics and distributing their supply internationally. This would help reduce costs to the pharmaceutical companies as well as ensure that drugs are used according to where the greatest need is, and therefore help strategically tackle global patterns of emerging resistance by supplying the most suitable drugs to each location. However, giving one organisation so much responsibility would require effective management to ensure that no companies or countries are able to exploit it.

Evidently, solving the issue of antibiotic resistance will be challenging and requires integrated global political leadership. Although the WHO’s 2015 Global Action Plan was a step in the right direction, there is more that should and can be done. In 2017, a year in which large political changes are imminent, it is more important than ever that the issue of antibiotic resistance is not forgotten. Worldwide collaborative effort will be the only way to devise innovative solutions to tackle this global health threat.